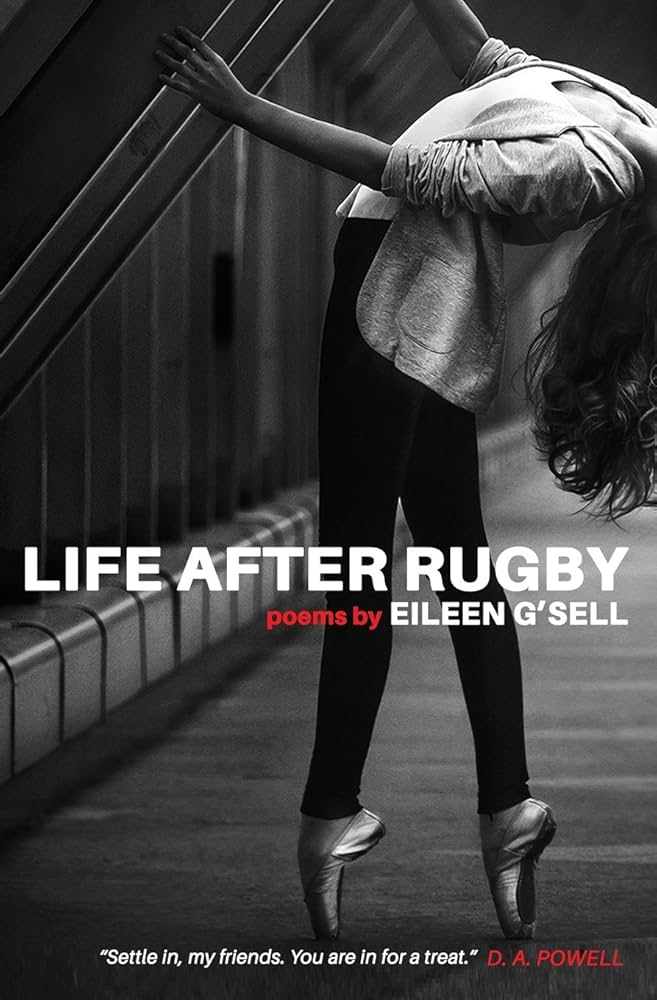

Life After Rugby

By Eileen G'Sell

There’s an inclusive, Whitmanesque charm to Life After Rugby, as if we’re being led by a keen observer through a cosmos of human beauty and complexity. It’s a little like Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, but in a more postmodern mood and key: the collection has no single speaker or stable point of view, nor any clear indicators of what cultural landscape each poem inhabits.

G’Sell has a veteran playwright’s ears and mind, conjuring all sorts of dictions, dialects, rhythms, and registers. Many of the poems read like dramatic monologues. The tight, soulful opener “Follow the Girl in the Red Boots” offers a playful invitation to listen to the book’s chorus of voices:

Follow the girl in the stolen shoes.

Follow the map that she made you.

Follow the soar of her certain song.

Plenty of people won’t.

The rest of the collection is pulsing and polyrhythmic. There’s the prose-poem elegance of “Women and Children” where “the equator twists into taffy” and “mountains sweet-talk snow.” Then there’s the stream-of-consciousness feminist romp “Deep Space Dialectic,” whose speaker fantasizes about kicking extraterrestrial ass, like an underwear-clad Sigourney Weaver in Aliens (“I take everything I can from the burning ship and prepare for the voyage home”). In “Like Good News from a Pretty Girl,” the voice gets colloquial and rough. Its closing line is a haymaker: “I refuse to make this beautiful.” In Life After Rugby, heterogeneity of character, tone, and perspective is the norm, the irreducible and insoluble fact of our shared existence.

A few poems gesture toward aphoristic, distilled wisdom. “Nothing solid saves,” warns a veteran of the sea. “Freedom is only lonely / when you let it be,” opines the “Ode to Mike Tyson.” Other fragments feel sublime, like this advice tendered in “World Cup”: “summer loss at the hem / of your dreams, sink your past / on the kindest ship.” In a more coded, shrouded way, “Real Butter” attests that “At best, life is hard,” but

The secret is not hiding

from the music at a party.

We are more important than the secret,

we are more practical than the secret,

we are more secret than the secret,

which makes us the secret.

The power of Life After Rugby derives equally from its evasion of “easy truths,” its reveling in the particular. “Impervious to Avalanche” exhibits a fierce longing and desire:

. . . I wish

to sleep

in perfect snow, die of sweet

collision, halfway to a heavy sky

and infinitely held. You say

you think I’d live through this,

you love as though it’s proven.

An excavated craving

for precision keeps me warm.

We curve as though

contrived of light, climb

as though it cures us.

And sometimes you just get a good story, unvarnished but well-told, like the one in “Blessed Are They, the Cinematic.” Animated, the speaker recalls a childhood encounter with a young St. Francis on the silver screen:

Francis sings in a gentle tenor, fleeing his jerk of a dad. He comes across Clare about one third through, and that’s where it gets good. Clare is the perfect Seventies Saint—long Breck hair and braless. . . . Her hair is blonde, her eyes are blue, she’s brutal as she turns her head. So brutal and pretty that no one can have her (not like he tries). . . . There are few lessons I recall more clearly than the lessons I learned from this feature film.

Other speakers can be side-splitting and even tough to take seriously. “Lately I’ve stopped seeing rich white men,” one speaker announces with flamboyant self-congratulation. In “After Camus Comes Out of a Coma,” another offers this bleary-eyed vision of redemption: “Sometimes I believe in heaven so that everyone can be adorable. The man who shits on the subway steps? He gets to be adorable. That bitch who mocks how loud you laugh? She gets to be adorable. The pit bull, the vulture, the substandard tip: they too will be adorable. Even I will be adorable. We all will be adorable.” In “Take Her Down,” a rhetorical shape-shifter opens with “I just want to give you / a run for your money” and ends with “I just want to tell you / the truth, for once.” And in the title poem a speaker almost spits, “Sometimes I want to rip you in half / to prove that I am hungry.”

On balance, though, Life After Rugby prefers beauty. Sometimes it comes off as mysterious (“roulade of lucent rationalizations, / ocean sad with conjugated rooms, the schooner is / shifting; the race is not rigged”), with titles rarely linked in any obvious way to rest of the poem. Elsewhere, it’s pure pleasure, like the high-octane, Thelma-and-Louise drift of “Drive”:

isn’t this what the wonderful women who didn’t raise us were always raving about? This leather and heat and soft seat wishing this rain and a midday singing so long this more than 3,000 miles more than Alaska more than my mother this drivetrain talent for transaxle searching this engine turning and turning again this torque approach to front-wheel living I was never your slushbox beautiful nothing I was agency movement clutch clutch clutch I was 500 hp gold and you know it the place it was I came from on that deathless night I came.

A word repeated in the collection is “sexless,” meaning a place—or soul—drained of rhythm, drained of life. Life After Rugby is anything but. It’s craft without artifice, and it succeeds so beautifully because, as the speaker of the closing poem puts it, “I have made light of many things / and that’s why we can see in here.”