Danielle Dutton and Martin Riker’s award-winning feminist press publishes overlooked experimental writers.

As individual writers, Associate Professor of English Danielle Dutton and Teaching Professor in English Martin Riker have each received high acclaim for their experimental novels and story collections.

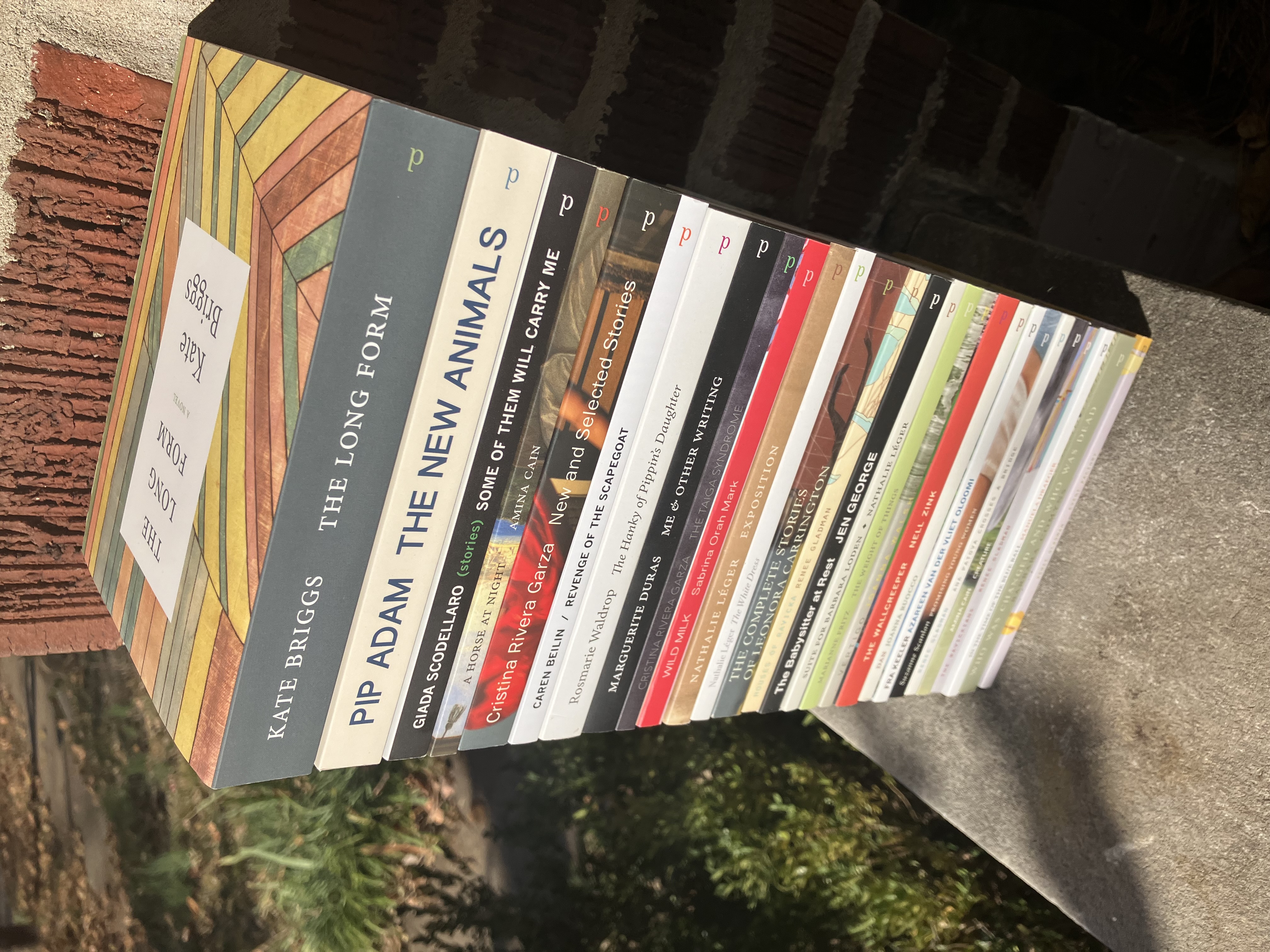

As a married couple, Dutton and Riker have also worked together to help aspiring writers find their own paths to publication. Their award-winning feminist press Dorothy, a publishing project, named after Dutton’s great-aunt, brings overlooked experimental writers into the spotlight. In October, the press released two new books: “The Long Form” by Kate Briggs and “The New Animals” by Pip Adam.

Recently, Dutton and Riker sat down with the Ampersand to discuss the challenges and rewards of independent publishing.

What inspired you to create Dorothy, a publishing project?

Danielle Dutton: Dorothy started with my sense that there wasn't a space in the literary culture that was championing innovative, brilliant, experimental fiction by women. So, we wanted to create a space to shine a spotlight on those writers and their books.

Martin Riker: It’s also an interesting thing to be a part of. Publishing can be collaborative and lively and rewarding in all sorts of ways. Finding a book you love, a voice that you love, coming from a writer who's not being published, and putting it out into the world.

What is unique about the project?

DD: Part of what makes Dorothy distinct is that we publish just two books a year. That was what we felt we could afford when we were putting up our own money to start a publishing house. And we felt like we could really lavish those two books and writers with our attention instead of just pushing them through some sort of publishing and publicity machine.

MR: In the publishing industry, the idea that you would publish only two books a year is in many ways impractical, because the systems of distribution are set up to support a larger list over multiple seasons. So, that's unusual. And then we have an odd name, “Dorothy, a publishing project,” and our books are all the same unusual size. Doing things differently from the big publishers comes with its problems, but also opportunities; we can present the books together as a set, for example, and make an event out of the annual launch. We don't have corporate resources, but we can champion individuality and care and attention. Our oddities give the press its identity, and it’s an identity that makes sense to us and is an important part of what we feel Dorothy is contributing to the culture.

Martin, you recently developed a publishing concentration for the English major. How can students in that concentration learn from Dorothy’s success?

MR: The publishing concentration is designed to give students a broad understanding of the many different types of publishing that go on in the US. We spend a lot of time with corporate New York publishing, but we also spend time with smaller independent and nonprofit publishers, including university presses. I teach two of the classes for the concentration, and I bring my own experiences to every class period, but it’s not Dorothy-centric, because the goal is for students to find what’s interesting to them.

We also try to balance the curriculum between practicality—learning how books are made—and critical analysis. With anything in academia, students come in and learn that things are more complicated than they might have expected or assumed — that’s certainly what the English major does. And I think to have that same experience in publishing makes sense.

What practical advice do you offer to students hoping to pursue careers in writing and publishing?

DD: This might sound cheesy, but I think it's important to keep making decisions with integrity. You can't know what you're going to be doing in five or 10 years, but you can make each decision you face, as you go, with an integrity that speaks to who you are and what matters to you about your work. In terms of practical advice, I am one of those people who thinks that a lot can be accomplished with dedication and hard work. If you really want to do something, it's about figuring out a way to do that thing and live. I waited tables during and after grad school, for example, which did not make me huge amounts of money, and it’s not something I’d put on a CV, but it meant I could write.

MR: I entirely agree. There's a difference between having a conventional sense of a career path and having a work ethic. One can move through the world in intuitive or unexpected ways and still really value work.

In addition to jumpstarting many writers’ careers, each of you has developed successful writing careers of your own. Are there any similarities between your respective writing styles?

MR: There's really no point of commonality, except that we both are weird.

DD: I might be weirder.

MR: You're a little weirder. But you're also a little cooler.

DD: Actually, while we’ve both written novels, I write in short forms more often than Marty does. So far, Marty has published two novels and is well into a third. My path was: story collection, novel, novel, and now I have a new collection coming out in April. So, I think I get attracted to shorter forms more often.

MR: One nice thing is that we edit each other. It’s very useful to have an in-house editor.

DD: Our son writes now, too, and is super opinionated. So now it’s like a three-way conversation in our house.

MR: He recently told me that I need to learn to use commas better. I was like, “I’m using them artistically.” But he just finished eighth grade, so he’s sticking to the rules.

What have been some of the most rewarding aspects of publishing other writers’ books?

DD: One of the main reasons I started the press was because I wanted to be able to have meaningful collaborative relationships with writers I admire. Working with Dorothy’s authors is very exciting for me. I’m also just a complete geek for book design; I love laying out a book and seeing how that transforms it. Something happens to a manuscript when you take it out of a Word document and put it into layout — you start to give it a visual structure that feels really magical. And then there's also the aspect of Dorothy being something that Marty and I do together. It's a part of our marriage; it's exactly the same age as our son.

MR: That we have this interesting project to work on together is one of my favorite things about Dorothy, in fact. We're very different people with very different tastes, but somehow we agree on almost everything for Dorothy.

In your view, how does Dorothy relate to the broader literary culture?

DD: Editorially, we’re always looking for something that we’re not seeing in the broader literary culture. It might be the sound of the language or some kind of formal innovation, but it has to be something new. I think the job of art is to remind us of how strange the world is, to wake us up to our lives, and that’s something we’re always looking for in a Dorothy book.

I'm also happy for the writers we publish to reach a wider audience, see their work in the world. And while it may be the case that Dorothy has some impact on the culture, I can’t think about it that way; it would mess me up. It's really important to us that we just keep doing what we’re doing.